As consumers’ health journeys become more individualised, The Future Laboratory explores how brands are tailoring nutrition, and what its effect might be on products as they appear on the shelves.

There are few consumer products more personal than what you eat. And yet for years, nutritional and dietary information has been built for the masses, with tools like the Food Pyramid and the Healthy Eating Plate acting as guides for how everyone should eat. ‘Different people have different needs and goals [when it comes to nutrition]…but existing tools and datasets are still one-size-fits-all and treat us all as if we’re the same person,’ says Sam Slover, founder of the nutrition platform Pinto.

Scientists are just beginning to understand the intricacies of nutrition and how it affects people uniquely. In June 2019, researchers at King’s College London and Massachusetts General Hospital announced results of Predict 1, a large nutritional study on how individuals’ blood marker levels respond to food. Even identical twins were found to have different reactions. Despite other similar genetic markers, twins shared just 37% of their gut microbes, only slightly higher than the 35% shared between two unrelated people. The findings suggest that our reaction to what we eat is down not only to a person’s genetics, but our environment, gut health, hours of sleep and other biological and environmental factors. The study sheds light on ‘why some people will lose weight on one diet, while others won’t,’ explained Professor Tim Spector, lead author to The Times. It also hints at a future where food will no longer be mass-produced, but individualized to personal health goals. And as scientists continue to research foods’ effects on the individual, startups and big brands alike are already forging ahead on how we might be able to make personalised nutrition a scalable reality.

Spector and his team of researchers recently founded a nutritional science startup Zoe which, alongside continuing the Predict study, is planning to launch its own app and at-home kit. Users will be able to test their glucose levels in order to choose foods that are optimal for their metabolism. Habit DNA is another startup that has made headlines recently with its meal kits designed around a person’s DNA markers and blood test results. For Maartje van den Berg, senior analyst at agribusiness market research firm RaboResearch, both these ventures offer a path to personalisation. ‘To have true personalised nutrition, there has to be some form of physical measurements such as DNA, gut bacteria or blood,’ she explains. But while measurement is one side of the personalised nutrition puzzle, the other is food data. ‘A personalised diet doesn’t necessarily need personalised products. You could assemble a tailored diet from products available at the supermarket, but you need that information about ingredients first,’ she adds.

We are now in an era where more and more consumers are going on specific diets – in the US alone, Americans on specific diets went from 14% in 2017 to 36% in 2018 (source: Fortune). In their journey for personalised nutrition, they are also seeking out better information, with ‘over half of consumers look at the nutrition facts panel or ingredient list often or always when making a purchasing decision’ according to the IFIC Foundation. In a survey of 3,000 American, British and German shoppers, ingredients supplier Beneo found that more consumers believed that the ingredients list was the most important attribute in motivating a purchase, over branding and product description. But despite this interest in nutrition, current labelling may not offer enough information to cater to specialised eating habits. Several companies are addressing this problem by combining databases and connected technology to go beyond the label and help consumers discern whether food fits their chosen diet.

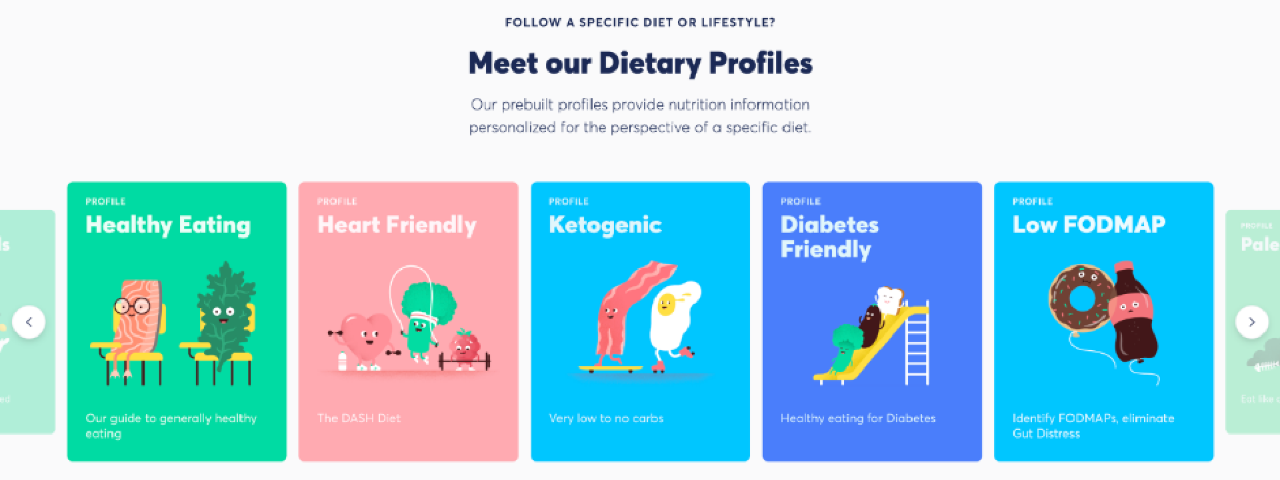

Starting off as a graduate project and now a fully-fledged business, Pinto is one such platform. Consisting of a website and app, users can set up their own nutritional goals – such as reducing salt intake or specify a diet like Ketogenic, – and when they scan an item’s barcode, Pinto will flag the nutritional information that matters most to achieving those goals. ‘We’ve always thought that a dream food label would work a bit differently,’ says Slover. ‘Rather than show everyone the same information, it would adapt to the needs and goals of each individual end user.’ Since Pinto’s database covers 85% of food in American grocery stores, thanks to its partnerships, a user could have a complex diet, where they are both lactose-intolerant, iron-deficient and low-FODMAP and Pinto will be able to navigate the dietary data to find the right food for them.

Similarly, grocery retailers are aiming to find ways to allow for mass personalisation of the food already on its shelves through apps. In the US, supermarket Kroger launched its OptUp app, which provides personalized product recommendations, scans and searches items to find nutrition facts and product alternatives. In the UK, Waitrose recently collaborated with Imperial College London and startup DNANudge on a trial of 200 pre-diabetic shoppers to see whether their food shopping was compatible with their DNA profile. Shoppers’ received a ‘thumbs up’ or ‘thumbs down’ on food they scanned based on how they match their genetic disposition. Similarly, Tesco works with Spoon Guru, an AI-powered app that was originally founded to flag allergens in food, but is now entering the tailored nutrition market.